De informatie die volgt is gebaseerd op de interpretatie van de lesgever. Zoals vaker het geval is in capoeira kunnen uitleg, regels en zelfs “feiten” verschillen per lesgever en groep. Het is belangrijk dit in het achterhoofd te houden, want er is geen één waarheid in capoeira.

Identiteit

volledige naam: Vicente Ferreira Pastinha

geboortedatum: 5 april 1889

overlijdensdatum: 13 november 1981

woonplaats: Salvador, Bahia, Brazilië

mentor: Benedito

stroming: Angola

school: Centro Esportivo de Capoeira Angola

bekend om:

- De preservatie van het oude capoeira.

- De heropleving van Capoeira Angola.

- Zijn levenswijsheid, metaforen en filosofie.

Genealogie

Mestre Pastinha leerde capoeira van een Afrikaan genaamd Benedito. Over zijn mentor is er verder zeer weinig bekend, net zoals over de mentor van Mestre Bimba. Hoewel hij minder leerlingen voortbracht dan Mestre Bimba, zijn de meeste van zijn leerlingen prominente en belangrijke capoeiras geworden in latere jaren. Zijn belangrijkste leerlingen waren:

- Aberrê

- Bigo

- Bobó

- Bola Sete

- Boca Rica

- Curió

- Gildo Alfinete

- Gigante

- João Pequeno

- João Grande

Biografie

Onderstaande tekst werd integraal gekopieerd uit het boek “Essential Capoeira: The Guide To Mastering The Art” van Ponciano Almeida.

The development of contemporary Capoeira is largely indebted to the work of Mestre Bimba and Mestre Pastinha in Brazil during the 1930s. Through their work, two major styles of Capoeira emerged, which are still practiced within Capoeira today. Capoeira Angola is considered to be the purer form of Capoeira, having moved less from the African roots of the game. Capoeira Angola places less emphasis on acrobatic moves and high kicks, instead focusing more on “malandragem,” the guile and cunning of the game. It is considered to be a slower game than Regional, and is played close to the ground. Developed by Mestre Bimba, Capoeira Regional is more widely practiced in contemporary Capoeira, and is seen to place more emphasis on harder, faster moves. In contemporary Capoeira, it is vital that you have an understanding of these two distinctive styles.

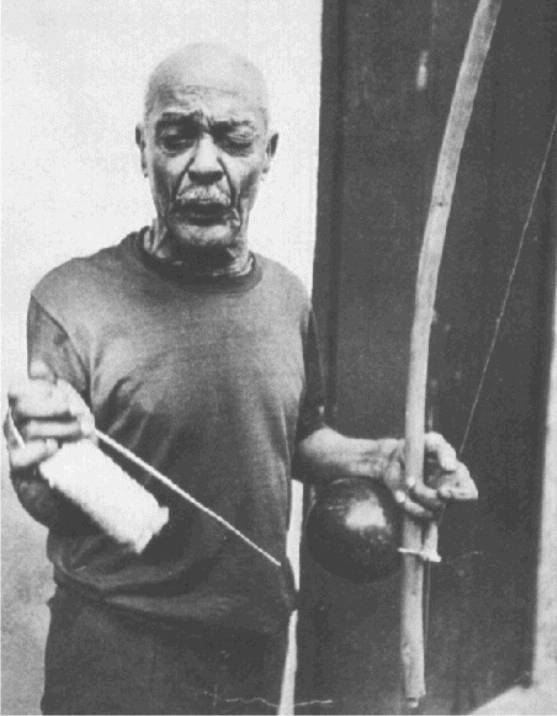

Born in Salvador, Bahia in 1889, Vicente Ferreira Pastinha is most commonly known for preserving the style of Capoeira Angola. He was small and slight from birth, and was bullied as a child. He was taken under the wing of an African named Benedito, who taught him Capoeira as a method of self-defense. Although he continued to have a slight build, Mestre Pastinha held his own against tough men, gaining a job as a bouncer in a local casino. He was also known to carry a sickle, which could be attached to his berimbau (a musical instrument), enabling it to become an offensive weapon for street fighting. Although he used Capoeira as a fighting art to defend himself on the streets, Mestre Pastinha was not simply a fighting man. He is more commonly known as the philosopher and storyteller of Capoeira, who dedicated his life to the love of the art. He loved to analyze Capoeira, to muse on its meanings and moves, and was the first popular Capoeirista to write a book on the subject.

Although many Capoeira Mestres respected the work of Mestre Bimba, others were opposed to the extent to which Capoeira had been modernized. Many resisted the changes made, and looked back to the origins of Capoeira and its African roots. Mestre Pastinha opened his academy a few years after Mestre Bimba, and sought to teach what he believed to be a purer form of Capoeira. This form of Capoeira became known as “Capoeira Angola.” The name Angola makes reference to the African slaves who first practiced the art, many of whom originated from Angola.

Like Mestre Bimba, Mestre Pastinha saw Capoeira as a discipline, and tried to distinguish it from the violent forms of Capoeira practiced on the street. He also wanted to improve the image of Capoeira, and by moving it away from the streets and in to the academy, he could provide some discipline. By adding a level of hierarchy and structure, he aimed to stop the use of violent and uncontrolled conduct. He placed great emphasis on the role of the mestre within the roda, believing that it was his duty to keep control. He also believed that his role as mestre gave him the responsibility to ensure that the traditions were continued. He aimed to keep Capoeira pure. Moves from other martial arts were banned, as were high kicks and any form of grappling. He also placed much emphasis on the music of Capoeira, composing many of his own rhythms and songs. Mestre Pastinha recognized the beauty and elegance the music added to the art, and even today you will not see Capoeira Angola played without the music. Mestre Pastinha also introduced uniforms to his academy. The colors black and yellow were taken from his favorite football team, Ypiranga, and are still used by many Angoleiros today.

Mestre Pastinha understood the fighting nature of Capoeira, but firmly believed that it could never be purely competitive. He placed much emphasis on the process and nature of the game, and not on winning and losing. He promoted fair play, manners, and loyalty, placing great emphasis on the “jogo de dentro” (the “inner game”). The inner game is essential to Capoeira Angola, since it demonstrates the student’s guile, cunning, and inner strength. Mestre Pastinha took a holistic approach to Capoeira, believing that a student’s development should be more than just physical. He acknowledged the psychological and spiritual aspects of Capoeira, and believed that it could be of great benefit to all. He is most famously quoted as saying: “Capoeira is for men, women, and children. The only ones who don’t learn Capoeira are those who don’t wish to.”

Mestre Pastinha’s approach to Capoeira attracted the attention of intellectuals and artists, many of whom became his friends. These connections helped him to open a school in a colonial building, establishing himself as the principal Angoleiro of his day. S0 successful was Mestre Pastinha’s Capoeira Angola that in the 1960s, tourists visited his academy to witness displays of “authentic Capoeira.” In the 1970s, however, his fortunes took a turn for the worse. His academy was repossessed by the Foundation for Artistic and Cultural Heritage, and was never returned. He lost all of his possessions, and even though he opened another academy, it never matched the scale and prestige of his former years. He eventually lost his eyesight and died penniless in an institution for the elderly. Like Mestre Bimba, he felt let down by the authorities.

It was assumed that after his death, Capoeira Angola would fade into obscurity, seen simply as a dying art for old men, and would be eclipsed by the more dynamic style of Regional. With the growing success of the Regional schools in Rio, it appeared that Angola had seen better days, and that the traditions it embraced were being pushed aside. During the 19805, however, there was a renewed interest in Afro-Brazilian culture, leading to an increased interest in Capoeira Angola. The Angola style was perceived to be a purer form of Capoeira, and thought to embody more of the traditions passed down from its African originators. In order to revive the dying art, the Grupo de Capoeira Angola Pelourinho was formed. This group called old Capoeira Angola mestres out of obscurity to train with them and, in defiance of the faster, acrobatic forms of the art, encouraged younger men to practice Capoeira Angola. It ceased to be an old man’s game, with younger Capoeiristas, such as Mestre Cobra Mansa, proving that it could be just as efficient a fighting technique as the Regional style.

Gespeelde berimbau ritmes

Volgens Waldeloir Rego speelde Mestre Pastinha volgende ritmes:

- Angola

- São Bento Grande

- São Bento Pequeno

- Santa Maria

- Cavalaria

- Amazonas

- Iúna

Meer informatie

Geschreven werken

The Heritage of Mestre Pastinha | Angelo Decânio Filho

Muziekalbums

Mestre Pastinha – Eternamente

Video’s

Pastinha! Uma Vida Pela Capoeira | Documentaire (PT)

Demonstratie door CECA in 1950 | Video

O Triste Fim De Mestre Pastinha | Video (PT)